saved from url=http://www.rsnz.govt.nz/archives/awards/ybook96/8.html

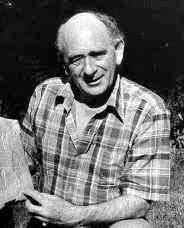

Howard Barraclough Fell

PhD DSc Edin FRSNZ FAAAS

1917-1994

HOWARD BARRACLOUGH ("BARRY") FELL was born on 6 June 1917 in Lewes, Sussex, England and died of heart failure in San Diego on 21 April 1994. His great-grandfather was John Barraclough Fell, an engineer and inventor of the "Fell" engine of revolutionary design enabling it to traverse steep inclines such as the Rimutakas. His father was Howard Barraclough Towne Fell, a respected merchant mariner who died in a shipboard fire at the young age of 33 when Barry was just six months old. His mother was Elsie Martha Fell who, when widowed, moved to Wellington where she became a successful businesswoman. She also wrote and published poetry. Barry came to New Zealand as a young child with his mother in the early 1920s and lived here -with a short break at university and in the army in Britain 1939-46 - until 1964 when he left New Zealand permanently for the United States. Barry married Renee ("Rene") Clarkson in 1942; they had two sons Roger and Julian and a daughter Veronica. Schooling and university

Barry attended Wellington College from 1930 to 1935 where he received prizes for his scholarship in science. As a young man Barry knew F. Hutchinson of Napier and accompanied him on field excursions around Hawkes Bay in search of fossils and other natural history objects. In 1935 he entered Victoria University College, then a college of the University of New Zealand, where he completed a BSc and MSc with First Class Honours in Botany in 1938.His awards included a Senior Scholarship in Botany and a Sir George Grey Scholarship in 1938, a Post Graduate Scholarship in Science (declined) and a Shirtcliffe Fellowship in 1939, the latter enabling him to study for his PhD at the University of Edinburgh 1939-41. He was awarded his PhD in 1941 with the thesis "Direct Development in the Ophiuroidea and its Causes". A measure of Barry's ability and potential as a scholar is that his first dozen papers covered such diverse subjects as echinoderm embryology, diet and leprosy, New Zealand biogeography, ancient Maori art, design of a bio-electric research apparatus and avian and human evolution. Five of these papers reached the pages of the journal Nature.

War service

By 1941 Barry had joined the British Army as a 2nd Lieutenant. Barry was of an age such that his earliest working life as a scientist was to be interrupted by World War II, like that of so many of his peers. In 1942 he transferred to the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers as a radar specialist and worked at the Antiaircraft Command School in Petersham, Surrey. He became associated with secret work on the development of radar and in the course of that travelled extensively to and fro across the Atlantic. Those students that later became aware of this phase of Barry's life viewed it with some wonder, considering that Barry was a specialist in the life histories of echinoderms! To them Barry did not seem to have any natural ability with mechanical or like things and they relished stories about Barry's misfortunes with his cars.Victoria University

After being released from army service in February 1946 with the rank of major and a commendation from the British War Office, Barry joined the staff of the Biology Department, Victoria University College, as Senior Lecturer in Zoology until 1957 when he became Associate Professor of Zoology. He quickly resumed his interests in echinoderms with great vigour and over the period 1946-1964 produced around 70 papers on the systematics, palaeontology and phylogeny of this group of animals. In particular he comprehensively documented the New Zealand fauna of sea stars and other echinoderms, a task that had been long needed. In his earlier days in Wellington he was one of a small group of local zoologists who met together at soires at the house of the noted entomologist G.V. Hudson. In 1948 he was President of the Association of Scientific Workers, guiding its early and at times difficult formative years.Barry's remarkable research productivity continued for some years after he left New Zealand in 1964 and established him as a distinguished authority on the echinoderms along with the great names of L. and A. Agassiz, H. L. Clark and E. Deichmann, all at the Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University. Many of his publications were works of great importance, often cited to this day. He provided new and unique perspectives on his discipline, a quality that became a feature of the later phase of his working life. Except for a few, though admittedly significant joint works on echinoderms, Barry was the sole author of these publications. Barry's work on the early pelagic life of most echinoderms committed him to a philosophy of long-distance, overseas dispersal to explain the distribution of these and other animals. He thus came into conflict with those who espoused the emerging theory of plate tectonics ("continental drift") that would account in a different way for animal distributions. Students of that time well recall Barry's vigorous debate in a class meeting with John Bradley, a member of the Geology Department, and found that Barry could be more than a gentle, scholarly, and retiring academic. They also remember Barry's overwhelming excitement and enthusiasm when he demonstrated to them the photographic evidence he had discovered allowing him to propose a revolutionary new reclassification of sea-stars. Barry made a lasting impression on undergraduate students as a lecturer, especially for the clarity of his presentations and the masterly way he could represent in blackboard sketches the complexity of invertebrate and vertebrate form and structure. For his contributions in the whole field of echinoderm biology, particularly fossil echinoids, Barry was awarded a DSc by the University of Edinburgh in 1955. He became a Fellow of The Royal Society of New Zealand in 1960, received the Society's Hector Research Medal in 1959, its Hutton Memorial Medal in 1962, and was also the Society's Hudson Lecturer. He became a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1964.

During his latter years at Victoria University Barry gathered around him a small but energetic group of graduate students who themselves became echinoderm specialists, including David L. Pawson who later joined the United States Museum of Natural History, Helen Rotman (nee Clark) and Alan Baker. They, and many others, found Barry to be a helpful, compassionate and greatly respected mentor, in marked contrast to the authoritarian and idiosyncratic stance that the then Head of Zoology, Lawrence Richardson, adopted towards many of his students and staff.

Harvard University

The contrast between these two men was marked and eventually a serious rift developed between them, sufficient for Barry to respond in 1964 to several invitations that had been made to him to join Harvard University's Museum of Comparative Zoology in Boston as Curator in Invertebrate Zoology. He later became Professor of Invertebrate Zoology, continuing his wide-ranging phylogenetic studies on echinoderms. As well he gained a singular reputation amongst undergraduate students for his innovative presentations and text-books on natural history of a style that had not been heard or seen for many years. He remained at Harvard until 1979, when he accepted voluntary retirement and he and Rene moved to San Diego, California.Harvard to San Diego: from echinoderms to epigraphy

Barry was an extraordinary linguist, learning to speak and write during his early student days in Maori, Latin, French, German and Ancient and Modern Greek. During his time at Edinburgh he learnt Danish fluently enough to lecture in it, and also spent time on the coast of northwest Scotland to learn Gaelic. Later he acquired a working knowledge of Russian, Sanskrit, Egyptian hieroglyphics and more than a dozen other languages of Africa, Asia and America. Around 1973, while still at Harvard and lecturing in marine biology, his coupled interests in numismatics, languages and animal distribution led him to switch his attention to ancient cultures, scripts and engraving on wood and stone (epigraphy). While there was some understandable official concern with this move, Harvard chose (and was able) to tolerate Barry's somewhat abrupt abandonment of echinoderm research for these new interests. At Harvard he was near to the great collections of inscribed tablets and like objects at the Smithsonian Institution and elsewhere and was able to make great use of the computing facilities available there in those early days in order to translate hitherto obscure ancient scripts. These enlarging interests, and the wholesale rejection of his findings that he evoked in the conservative establishment, led him to found the Epigraphic Society in 1974, as its first President, so as to provide an outlet for his writings. Today, more than 20 years on, the Society flourishes, with worldwide membership.Barry quickly became totally immersed in epigraphy and accumulated an encyclopaedic knowledge in this field, publishing three controversial but very popular books on pre-Columbian migrations of humans to North America from Europe. He was immensely and very ably assisted in these endeavours by his wife Rene. His books not only resulted in great debate and criticism in the United States in particular, but also elicited a flood of epigraphic material sent to him from all over the world, allowing him to develop his ideas further. Barry began to publish his specific findings almost wholly in the journal "The Polynesian Epigraphic Society Occasional Publications", eventually to become broadened in scope to "The Epigraphic Society Occasional Papers". The essence of these many and wide-ranging publications was a demonstration, at least to Barry's (and others) complete satisfaction, of an ancient link between North African (Phoenician or Carthaginian) peoples, trade routes and cultural influences and Polynesian, particularly Maori, cultures. Barry was Visiting Professor at the University of Tripoli in 1978 and overnight became a national hero for his demonstration of how to translate ancient ciphers and funerary inscriptions into Arabic and was the recipient of the Tripoli Prize for Arab History in 1980. In addition, he claimed to demonstrate an extensive pre-Columbian colonisation of North America from North Africa and Europe - a source of much of the criticism levelled at him. In recognition of his work, Barry received a string of Honorary Fellowships and awards from scientific and other societies from the United States to Europe, Africa and Polynesia.

It is beyond the scope of this obituary and the competence of its author to evaluate Fell's propositions, suffice to say that they have been widely accepted by some and considered as heretical, and certainly extravagant, by others. Barry's adversaries in this lengthy saga were envious of his success and frequently bitter in their condemnation of him and his theories though they were often unable to document the evidence necessary to reject them. Many of his critics of the 1970s and 1980s could well have benefited from the advice given to Archbishop Desmond Tutu by his mother: "Do not raise your voice, strengthen your argument."

Barry's additional interests in astronomy, sculpture, poetry and music, and his deep commitment to scholarship inevitably led him into a somewhat ascetic life as a pathfinder in biology, linguistics and epigraphy. He would undoubtedly have wished to carry it on in this manner, without the controversy that his writings had generated, but that was not to be. His singular contributions to knowledge can perhaps be best expressed in the words that Barry himself once used in honouring his own professor at Victoria University College, Harry Borrer Kirk: Exigi monumentum aere perennis (Horace) - "I have reared a monument more lasting than bronze."

Peter H J Castle

Acknowledgements

The writer is grateful to Rene Fell, David L. Pawson and Helen E. Rotman for providing information on Barry Fell's early life and activities both in New Zealand and United States.Bibliography

Papers and books 1940-1983

1940 Economic importance of Chalcoponera metallica. Nature, London 145: 707. Origin of the vertebrate coelom. Nature, London 145: 906. Culture in vitro of the excised embryo of an ophiuroid. Nature, London 146: 173. Wheat diet and leprosy. Nature, London 146: 497. The fauna of New Zealand. Nature, London 147: 253. 1941 The direct development of a New Zealand ophiuroid. Quart. J. Micr. Sci. n.s. 82: 377-441. Probable direct development of some New Zealand ophiuroids. Trans. Proc. Roy. Soc. N.Z. 71 (1): 25-26. The pictographic art of the ancient Maori of New Zealand. Man 61: 85-88. 1945 A revision of the current theory of echinoderm embryology. Trans. Proc. Roy. Soc. N.Z. 75 (2): 73-101. New bio-electric research apparatus. N. Z. Sci. Rev. 3 (1): 8-9. Wild life management. N.Z. Sci. Rev. 3 (2): 14. Polynesian origins. An American view. N.Z. Sci. Rev. 3 (3): 8. Review of: "Earth Beneath" by C.A. Cotton. N.Z. Sci. Rev. 3 (3): 14. 1946 The embryology of the viviparous ophiuroid Amphipholis squamata Delle Chiaje. Trans. Proc. Roy. Soc. N.Z. 75 (4): 419-464. Avian evolution in New Zealand. Nature, London 157: 272. Tailed man, Homo caudatus L. N.Z. Sci. Rev .4(2): 24-25. 1947 A giant heart-urchin, Brissus gigas, n. sp. from New Zealand. Rec. Auckland Inst. Mus. 3: 145-150. Ophiomyxa duskiensis, a new ophiuroid from the Southern Fiords. Trans. Proc. Roy. Soc. N.Z. 76 (3): 421-422. The migration of the New Zealand bronze cuckoo Chalcites lucidus lucidus (Gmelin). Trans. Roy. Soc. N.Z. 76: 504-515. 1948 Echinoderm embryology and the origin of chordates. Biol. Rev. Cambridge 23: 81-107. Marine zoology in Denmark (Review). N.Z. Sci. Rev. 6(1): 17. Viviparity in New Zealand skinks. N.Z. Sci. Rev. 6(2): 38. H.B. Kirk (Obituary). N.Z Sci. Rev. 6(2): 43-44. Science and the public. N.Z. Sci. Rev. 6(5): 87-89. A key to the littoral asteroids of New Zealand. Tuatara, Wellington N.Z. 1(1): 20-23. A key to the sea urchins of New Zealand. Tuatara, Wellington N.Z. 1(3): 6-13. 1949 An echinoid fron the Tertiary (Janjukian) of South Australia. Brochopleurus australiae sp. nov. Mem. Nat. Mus. Melbourne 6: 17-19. The occurrence of Australian echinoids in New Zealand waters. Rec. Auckland Inst. Mus. 3(6): 343-346. Review of: "Animals Alive" by A.H. Clark. N.Z. Sci. Rev. 7(7): 131. The constitution and relations of the New Zealand echinoderm fauna. Trans. Roy. Soc. N.Z. 77: 208-212. New Zealand littoral ophiuroids. Tuatara, Wellington N.Z. 2(3): 121-129. 1950 A Triassic echinoid from New Zealand. Trans. Roy. Soc. N.Z. 78(1): 83-85. A key to the sea urchins of New Zealand. Additional species. Tuatara, Wellington N.Z. 3(1): 42. New Zealand crinoids. Tuatara, Wellington N.Z. 3(2): 78-85. The Kirk Collection of sponges in the Zoology Museum, Victoria University College. Zool. Publ. Victoria Univ.Coll. N.Z. No.4: 112 pp. Review of: "The Takahe: accounts of field investigations on Notornis" by R.H.D. Stidolph. N.Z. Sci. Rev. 9(8): 135. 1951 Some off-shore and deep-sea ophiuroids from New Zealand waters. Zool. Publ. Victoria Univ. Coll. N.Z. No.13: 1-4. 1952 Rediscovery of the ophiuroid genus Ctenamphiura Verrill. Nature, London 170: 327. An upper Cretaceous asteroid from New Zealand. Rec. Canterbury (N.Z.) Mus. 6(2): 143-147. Echinoderms from southern New Zealand. Zool. Publ. Victoria Univ. Coll. N.Z. No.18: 1-37. Review of: "Embryos and ancestors" by G.R. de Beer. N.Z. Sci. Rev. 10(4): 55. 1953 Echinoderms from the Subantarctic Islands of New Zealand: Asteroidea, Ophiuroidea, and Echinoidea. Cape Expedition Series, Scientific Results of the New Zealand Subantarctic Expedition, 1941-45, No.18. Dom. Mus. Rec. Zool. Wellington 2(2): 72-111. The origins and migrations of Australasian echinoderm faunas since the Mesozoic. Trans. Roy. Soc. N.Z. 81(2): 245-255. The first century of New Zealand zoology, 1769-1868, comprising abstracts and extracts from early works in the New Zealand fauna. (Compiled by H.B Fell and others). Dept. of Zoology, Victoria University College, Wellington. 90 pp. 1954 New Zealand fossil Asterozoa 3. Odontaster priscus sp. nov. from the Jurassic. Trans. Roy. Soc. N.Z. 82(3): 817-819. Tertiary and Recent Echinoidea of New Zealand. Cidaridae. Palaeont. Bull. N.Z. 23: 62 pp. The Anglo-Saxon penny in daily life. N.Z. Numismatic Jour. 8(1&2): 1-10. The Plantagenet penny in daily life. N.Z. Numismatic Jour. 8(1&2): 11-15. Notes on echinoderms from Cape Palliser. N.Z. Jour. Sci.Tech.B. (35)(5): 447-448. 1956 Tertiary sea temperatures in Australia and New Zealand, from evidence of fossil echinoderms. Proc. Int. Congr. Zool., Copenhagen 14: 103-104. New Zealand fossil Asterozoa, 2 Hippasteria antiqua n. sp. from the Upper Cretaceous. Rec. Canterbury (N.Z.) Mus. 7: 11-12. 1957 Report on the echinoderms. P.33 (Appendix 5) in Knox, G.A., General account of the Chatham Islands 1954 Expedition. Bull. N.Z. Dept. Sci. Industr. Res. No.122: 1-37. 1958 Deep-sea echinoderms of New Zealand. Zool. Publ. Vict.oria Univ. N.Z. No 24: 1-40. The Pogonophora. Tuatara, Wellington N.Z. 7(2): 43-47. 1959 Starfishes of New Zealand. Tuatara, Wellington N.Z. 7(3): 127-142. (with Clark, H.E). Anareaster, a new genus of Asteroidea from Antarctica. Trans. Roy. Soc. N.Z. 87 (1 & 2): 185-187. 1960 Archibenthal and littoral echinoderms of the Chatham Islands. Bull. N.Z. Dept. Sci. Industr. Res. No.139: 55-75. Synoptic keys to the genera of Ophiuroidea. Zool. Publ.. Vict.oria Univ. N.Z. No.26: 1-44. Echinodermata In Encyclopedia of Science and Technology. McGraw-Hill, New York. (Various articles). Marine shallow-water fauna of Wellington. Roy. Soc. of N.Z. (Handbook: Science in Wellington) pp. 20-22. 1961 in Anon. New "living fossil" discovered. The Times. Dec. 21. Light verse - when cave wetas roamed the Ark. Tuatara, Wellington N.Z. 9(2): 79. A dangerous sea-urchin. Tuatara, Wellington N.Z. 9(2): 84. Food in the bush. Tuatara, Wellington N.Z. 9(2): 85. Challenger material in Wellington. Tuatara, Wellington N.Z. 9(2): 85-86 New genera and species of Ophiuroidea from Antarctica. Trans. Roy. Soc. N.Z. 88(4): 839-841. A bipolar genus of Ophiuroidea, Toporkovia Djakonov. Zool. Zh. 40: 1257-1258. (In Russian with English summary). The fauna of the Ross Sea. Part 1. Ophiuroidea. Mem. N.Z. Oceanogr. Inst. 18: 1-79. 1962 A surviving somasteroid from the eastern Pacific Ocean. Science 136: 633-636. A living somasteroid, Platasterias latiradiata Gray. Paleont. Kans. Echinodermata 6: 1-16. A revision of the major genera of amphiurid Ophiuroidea. Trans. Roy. Soc. N.Z.(Zool.) 2: 1-26. A revised classification of the Australian Amphiuridae (Ophiuroidea). Proc. Linn. Soc. N.S.W. 87: 79-83. A living somasteroid. Zool. Zh. 41: 1353-1366. (In Russian with English summary). Evidence for the validity of Matsumoto's classification of the Ophiuroidea. Publ. Seto Mar. Biol. Lab. 10: 145-152. Embryological evidence of evolutionary trends in some temnopleurid echinoids. In Leeper, G.W. (Ed). The Evolution of Living Organisms. (Symp. Roy. Soc. Victoria, Melbourne. Pp. 307-310). A new Cretaceous echinoid from the Franciscian Formation of California. Trans. Roy. Soc. N.Z. 2(2): 27-30. West-wind drift dispersal of echinoderms in the Southern Hemisphere. Nature, London 193: 759-761. A classification of echinoderms. Tuatara,Wellington N.Z. 10(3): 138-140. Native Sea Stars. A.H. & A.W Reed, Wellington. 64 pp. Saint Cuthbert's beads and thunderstones; sidelights on the search for living fossils. Proc. Roy. Soc. N.Z. 91: 101-113. 1963 The phylogeny of sea-stars. Phil. Trans. 246B: 381-435. The evolution of echinoderms. Rep. Smithson. Inst. 1962: 457-490. A new family and genus of Somasteroidea. Trans. Roy. Soc. N.Z.(Zool.) 3(13): 143-146. The oldest sea stars. Sea Frontiers 9(3): 168-177. The spatangid echinoids of New Zealand. Zool. Publ. Vict.oria Univ. N.Z. No.32: 1-8. (with Follett, W.I. & Dempster, L.J.). Comments on the proposed designation of a lectotype for Asterias nodosa Linnaeus, 1758, and addition of the generic name Protoreaster Doderlein, 1916, to the Official List. Bull. Zool. Nom. 20: 262-263. 1964 Oligocene echinoids from Trelissic Basin, New Zealand. Trans. Roy. Soc. N.Z.(Zool.) 4(15): 201-205. New genera of Tertiary echinoids from Victoria, Australia. Mem. Nat. Mus. Vict. No.26: 211-217. A list of Echinodermata collected by N.Z.O.I. from Milford Sound. Bull. N.Z. Dept. Scient. Ind. Res. No.157 (Mem. N.Z. Oceanogr. Inst. No.17): 95. Intraspecific variation in a New Zealand sea-star. Tuatara Wellington, N.Z. 12(3): 186. 1965 Ancestry of sea-stars (part). Nature, London 208: 768-769. (with Pawson, D.L.) A revised classification of the dendrochirote holothurians. Breviora No. 214: 1-7. 1966 Ancient echinoderms in modern seas. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. Ann Rev. 4:233-245. Ecology of crinoids. Chapter 2. Pp. 49-62 in Boolootian, R.A.(Ed). Physiology of Echinodermata. (New York: Wiley Interscience Publishers). The ecology of ophiuroids. Chapter 6. Pp. 129-143 in Boolootian, R.A(Ed). Physiology of Echinodermata. (New York: Wiley Interscience Publishers.). Cidaroids. Pp. 312-339 in Moore, R.C.(Ed). Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology. Part U. Echinodermata 3, vol.1. Geological Society of America Inc: University of Kansas Press. (with Melville, R.V. & Pawson, D.L.) Euechinoids. Pp. 339-366a in Moore, R.C.(Ed). Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology. Part U. Echinodermata 3, vol.1. Geological Society of America Inc: University of Kansas Press. (with Moore, R.C.) General features and relationships of echinozoans. Pp. 108-118 in Moore, R.C.(Ed). Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology. Part U. Echinodermata 3, vol.1. Geological Society of America Inc: University of Kansas Press. (with Moore, R.C.) Homology of echinozoan rays. Pp. 119-31in Moore, R.C.(Ed). Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology. Part U. Echinodermata 3, vol.1. Geological Society of America Inc: University of Kansas Press. (with Pawson, D.L.). General biology of echinoderms. Chapter 1 Pp. 1-48 in Boolootian, R.A.(Ed). Physiology of Echinodermata. (New York: Wiley Interscience Publishers.). (with Pawson, D.L.) Echinacea. Pp. 367-440 in Moore, R.C.(Ed). Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology. Part U. Echinodermata 3, vol.2. Geological Society of America Inc: University of Kansas Press. 1967 Resolution of coriolis parameters for former epochs. Nature, London 214: 1192-1198. Biological application of sea-floor photography. Pp. 207-221 in Hersey, J.B. (Ed). Deep-sea Photography. The early evolution of the Echinozoa. Breviora No.219, 1965: 1-17. Echinoderm ontogeny. Pp. 60-85 in Moore, R.C.(Ed). Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology. Part S. Echinodermata 1. Geological Society of America Inc: University of Kansas Press. Cretaceous and Tertiary surface currents of the oceans. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. Ann. Rev. 5: 31-341. 1968 The biogeography and paleoecology of Ordovician seas. Pp. 139-162 in Drake, E.T.(Ed). Evolution and Environment. Yale University Press, New Haven and London. 1969 (with Dawsey, S.) Asteroidea. American Geographical Society, New York (Antarctic map folio series) No.11: 410. (with Faulkner, D.) Stachelhauter. Du 338: 261-271. (with Holzinger, T. & Sherraden, M.). Ophiuroidea. American Geographical Society, New York (Antarctic map folio series) No.11: 42-43. (with Henderson, R.A.). Taimanawa, a new genus of brissid echinoids from Tertiary and Recent Indo-West Pacific with a review of the related genera Brissopatagus and Gillechinus. Breviora No.320: 1-29. Review of: "A monograph of the existing crinoids" by A.H. & A. M. Clark, 1967. Quart Rev. Biol. 44: 91-93. 1970 Echinoderms: sirens of the sea. Oceans Mag. 3(1): 52-59. 1971 (with Faulkner, D.). Crinoids and the dawn of deep-sea research. Fauna Rancho Mirage No.3: 5-13. The Tethyan legacy - the origin and dispersion of Indian Ocean echinoids. J. Mar. Biol. Ass. India 13(1-2): 78-81. Phylum Echinodermata. Pp. 776-837 in Marshall, A.J. & Williams, W.D. (Eds). Parker and Haswell's Textbook of Zoology, 7th edition. Macmillan, London. (with Hotchkiss, F.H.C.). Zoogeographical implications of a Paleogene echinoid from East Antarctica. J. Roy. Soc. N.Z. 2(3): 369-372. 1974 Life, space and time : A course in evironmental biology. Harper & Row Publishers, New York. xiv + 417 pp. From sea stars to star charts. Museum of Comparative Zoology. Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. 4(2): 4-5. 1975 Introduction to marine biology. Harper & Row Publishers, New York. x + 356 pp. Maoris from the Mediterranean. New Zealand Listener, Feb.22: 10-13. Maoris from the Mediterranean. Part Two. New Zealand Listener, Mar.1: 20-21. (with Carter, G.F. 1975). In honor of Harold S. Gladwin. ESOP 2, No.25: 1-18. 1976 (with Faulkner, D.). Dwellers in the sea. Reader's Digest Press, New York. 199 pp. America B.C. Times Books, New York. vii + 312 pp. 1978 America B.C. Simon & Schuster, New York. 1980 Saga America. Times Books, New York. xvii + 425 pp. 1982 Bronze Age America. Little Brown & Company. 304 pp. 1983 Christian messages in old Irish script deciphered from rock carvings in West Virginia. Wonderful West Virginia. 47(1): 12-19. Epigraphic articles (photocopied, 1973-74)

These had a limited distribution and might best be described as "grey" literature.

1973 A basic Egypto-Polynesian word list. Museum of Comparative Zoology. Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. P.36. Egypto-Polynesian phonetics. Museum of Comparative Zoology. Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. Pp.38-52. Egypto-Polynesian syntax. Museum of Comparative Zoology. Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. Pp.54-61. Egypto-Polynesian alphabets. 1. Semitic series of Java and Sulawesi. Museum of Comparative Zoology. Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. Pp.63-67. Egypto-Polynesian steles. 1. A fourth-century edict from Suku Pyramid. Museum of Comparative Zoology. Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. Pp.69-79. Egypto-Polynesian steles. 2. Cheribon texts inscribed in Phoenician script. Museum of Comparative Zoology. Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. Pp.81-89. Evolution of the Egypto-Polynesian scripts. Museum of Comparative Zoology. Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. Pp.91-102. Egypto-Polynesian alphabets: 2, The Suku Pyramid sign series and inferred models. Museum of Comparative Zoology. Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. Pp.103-108. Polynesian tablets and Protopolynesian. A newly deciphered European tongue of the Minoan subgroup. The Phaistos disk ca 1600 B.C. Museum of Comparative Zoology. Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. Pp.200-217. 1974 Minoan features of a Polynesian tablet newly deciphered. Museum of Comparative Zoology. Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. Pp.240-247. Polynesian tablets. The testament of Te Ronga. A decipherment of tablet 129773 in the collection of the U.S. National Museum. 1. Kaiwi vocabulary. Museum of Comparative Zoology. Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. Pp.248-269. Epigraphic Society publications (1975-1993)

All but a few of these were published in The Polynesian Epigraphic Society Occasional Publications (referred to below as PESOP for convenience; 1974), later to becomeThe Epigraphic Society Occasional Publications (ESOP; 1974-1989) and still laterThe Epigraphic Society Occasional Papers (ESOP; 1990-1993). Fell published just over 200 papers in this journal, all under the name "B. Fell" or "Barry Fell", a few jointly with other authors, as well as many separate letters and responses. These latter are not included in the list below. At the time of writing, Volume 23 of ESOP, containing the last of Barry's contributions and additional biographical information, was still in preparation.

1974 An Egyptian shipwreck at Pitcairn Island. PESOP No.1: 1-3. Polynesian epigraphy. A report to the Society. PESOP No.2: 1-2. The ancient Maori votive stele of the Pyramid of Ra on Mount Lavu in eastern Java. PESOP No.3: 1-6. Numerals on ancient Maori steles. PESOP No.4: 1-8. Ritual of the dawn: fragments of ancient Maurian charts in New Zealand Maori. PESOP No.5: 1-6. Ancient Maori inscriptions of North Africa. 1. The bilingual Latin-Maori stele of Kaiu from Thullium. PESOP No.6: 1-6. Ancient Maori inscriptions of North Africa. 2. The bilingual Latin-Maori stele of Rapa from Thullium. PESOP No.7: 1-5. Ancient Maori inscriptions from North Africa. 3. The bilingual Latin-Maori stele of Fawasa, Priest of the Oracle of Rono. PESOP No.8:1-4. Ancient Maori inscriptions from North Africa. 4. The bilingual Punic-Maori stele of Weka from Bordj-Zubia near Oued-Meliz, Tunisia. PESOP No. 9:1-4. Distribution of ancient Maori inscriptions written in Maurian (Numidian) script. PESOP No.10: 1-43. Ancient Maori inscriptions of North Africa. 5. The bilingual Latin-Maori stele of Zakatutu from Thullium. PESOP No. 11: 1-3. Chronology of ancient Maori scripts. PESOP No.12: 1-7. An ancient Maori inscription from Dakumba, Fiji. PESOP No.13: 1-6. Carthaginian and other graffiti from West Irian caves. PESOP No. 14: 1-3. Ancient Maori mathematical and scientific hieroglyphs. PESOP No. 15: 1-4. The Treaty of Taranaki, a mediaeval stele of New Zealand. PESOP No. 16: 1-5. Newly deciphered naval records of Ptolemy III. PESOP No.17: 1-2. A proposition by Eratosthenes. An astronomer of the delta country. PESOP No.18: 1-6. Maui on Eratosthenes. An additional fragment from Sosorra. PESOP No. 19. The Polynesian discovery of America 231 B.C. PESOP 2, No.21: 1-8. An ancient Polynesian star atlas of 232 B.C. Part 1. A mariner's guide to finding the celestial North Pole. PESOP 2, No.22: 1-4. Karl Stolp's discovery of la Casa Pintada in 1885 translated from the original report by Mina Brand. PESOP 2, No.23: 1-5. Mailu, an African language of eastern Papua New Guinea. ESOP 2, No.26: 1-20. An ecliptic rebus by Maui. ESOP 2, No.28: 1-2. 1975 An ancient Polynesian star atlas of 232 B.C. Part 2. "The zodiac tips upside-down" - Maui crosses the equator. ESOP 2, No.30: 1-4. Phonetic mutation in Egypto-Polynesian languages. ESOP 2, No.32: 1-15. Libyan visitors to Scandanavia in the early Bronze age. ESOP 2, No.34: 1-3. An ancient Maori text in Libyan script from Otaki, New Zealand. ESOP 2, No.38: 1-9. Protosanskrit, a Bronze Age language of Mohenjo Daro. ESOP 2, No.39: 1-32. East African vocabulary in New Guinea and Polynesia. ESOP 2, No.42: l-3. - (with Reinert, E.P.). Iberian inscriptions in Paraguay, ca 4th c. B.C. ESOP 2, No.43: 1-10. An Iberian-Punic stele of Hanno. ESOP 2, No.44: 1-3. Epigraphy of the Susquehanna steles. ESOP 2, No.45: 1-8. 1976 A fifth-century Moroccan emigration to America. ESOP 3 (1), No.46: 1-10. An Arabic dialect in ancient Moroccan inscriptions. ESOP 3 (1), No.48: 1-12. Celtic Iberian inscriptions in New England. A preliminary report submitted to the Epigraphic Society, the Early Sites Research Society,and the New England Antiquities Research Association. ESOP 3 (1), No.50: 1-5. (with Williams, J.). Inscribed Sarsen stones in Vermont. ESOP 3 (1), No.53: 1-2. Ancient Arabic script and vocabulary of the Algonquian Indians. ESOP 3 (1), No.54: 1-3. A Celtiberian (Gadelic) law-tablet from Ourique, Portugal. ESOP 3 (1), No.55: 1-3. A dialect of Ancient Greek from south-eastern Spain. ESOP 3(1), No.56: 1-6. Ancient Iberian magnetic compass dials from Liria, Spain. ESOP 3 (1), No.57: 1-6. A Celtiberian funeral stele in Navarra, Spain, inscribed in Ogam. ESOP 3 (1), No.58: 1-2. The roots of Libyan. ESOP 3 (2), No.63: 1-6. The structure of the Zuni language. ESOP 3 (2), No.64: 1-10. The Romano-Celtic phase at Mystery Hill, New Hampshire, in New England. ESOP 3 (2), No.67: 1-3. Possible Libyan petromanteia in Quebec. ESOP 3 (2), No. 72: 1-5. The Pima myth of Persephone. ESOP 3 (2), No.74: 1-7. Two ancient Iberian hospitality pledges and their texts. ESOP 3 (2), No.75: 1-3. The etymology of some ancient American inscriptions. ESOP 3 (2), No.76: 1-6. 1977 The Minoan language - Linear A decipherment. ESOP 4 (1), No.77: 1-67. A letter from Hiram III, ca 540 B.C. ESOP 4 (1), No.78: 1-12. The Phaistos Disk ca1600 B.C. ESOP 4 (1), No.79: 1-79. A dialect of Minoan from Cyprus. ESOP 4 (1), No.80: 1-5. Takhelne, a living Celtiberian language of North America. ESOP 4 (2), No.92: 1-28. Amphorettas from Maine and Iberia. ESOP 4 (2), No.96: 1-3. 1978 Etruscan. ESOP 5 (1), No.100: 1-48. Some Celtic phalli. ESOP 5 (2), No.110: 1-48. Iberic in Norway. ESOP 5 (2), No. 113: 1-4. Eastern Norse runes of the Roman Iron Age. ESOP 5 (2), No. 115: 1-3. 1979 Ogam inscriptions from North and South Africa. ESOP 6 (1), No.116: 23-26. A late Roman inscription from the Canary Islands. ESOP 6 (1), No.117: 27-29. Tamacheq, a living dialect of ancient Libyan. ESOP 6 (1), No. 118: 31-33. Berber roots in Polynesian. ESOP 6 (1), No.119: 35-42. An ancient Libyan mariner's prayer. ESOP 6 (1), No.120: 43-44. A basic Egypto-Polynesian word list. ESOP 6 (1), No.121: 45-83. An inscription of King Masinissa ca.139 B.C. ESOP 6 (1), No.122: 85-88. Horse racing in ancient Libya. ESOP 6 (1), No.123: 89-92. Plague and the worship of the cat goddess in ancient Libya. ESOP 6 (1), No.125: 97-100. Hunting inscriptions of the ancient Libyans. ESOP 6 (1), No.126: 101-108. Inscriptions on Kentucky sculptures. ESOP 6 (1), No.128: 115-116. Medical terminology of the Micmac and Abenaki languages. ESOP 7 (1), No.139: 7-20. Takhelne, a North American Celtic language - Part 2 - the radicals. ESOP 7 (1), No.140: 21-42. Additional Lirian compass dial inscriptions from Spain and New Mexico. ESOP 7 (1), No.142: 51-53. Prepositions in hieroglyphic Micmac. ESOP 7 (2), No.156: 143-145. The Micmac manuscripts. ESOP 7 (2), No.157: 146-150. An ancient Libyan epitaph from Nubia. ESOP 7 (2), No.159: 155-157. The Micmac manuscripts - 2. ESOP 7 (2), No.162: 167-181. How Champollion solved the Hieratic script. ESOP 7 (2), No.167: 208-209. A cartouche of Shishonq from Almunecar, southern Spain. ESOP 7 (2), No.171: 233. A Ptolemaic tetradrachm from Queensland. ESOP 7 (2), No.172: 234. Libyan anubis in southern Spain. ESOP 7 (2), No.173: 235. How Egyptians really wrote. ESOP 7 (2), No.177: 243-245. Epigraphy of three Sinai steles. ESOP 7 (2), No.178: 246-247. 1980 An ancient Zodiac from Inyo, California. ESOP 8 (1), No.179: 9-14. The name Amon-Shishonq in Ptolemaic use. ESOP 8 (1), No.181: 21-23. Thirty-two Cypro-Minoan signatures to the British Treaty with the Abenaki people, signed July 25th 1727. ESOP 8 (1), No.185: 44-49. Noah at Nineveh-a Koranic chant of the Pima tribe. ESOP 8 (1), No.186: 50-56. The Islamic inscriptions of America. ESOP 8 (1), No.187: 57-76. Cypro-Minoan syllabaries of America. ESOP 8 (1), No. 188: 77-82. Oak Island-and after. ESOP 8 (2), No.193: 136-137. Inscriptions from North Africa. ESOP 8 (2), No.197: 152-156. An elephant petroglyph in Glen Canyon, Colorado. ESOP 8 (2): 161. Two Lusitanian memorials. ESOP 8 (2), No.200: 165-167. Ogam consainne. ESOP 8 (2). 1981 Decipherment and translation of the Newberry tablet from northern Michigan. ESOP 9 (2), No.218: 132-136. 1982 The Bohuslan culture (Bronze Age Norse) in North America. ESOP 10 (1), No.231: 17-29. 1983 Old Irish rock inscriptions from West Virginia. ESOP 11 (1), No.252: 37-51. The Ogam boar of Castulo. ESOP 11 (1): 56. Foulis Wester. ESOP 11 (1), No.254: 58-61. Meanings of the idiograms. ESOP 11 (1), No.257: 102-105. Primstav-an Old Norse hieroglyphic calendar. ESOP 11 (2), No.260: 120-128. American Bighorns or Old World imports. ESOP 11 (2), No.264: 167-169. Medical inscriptions from Tripolitania. ESOP 11 (2), No.268: 204-208. Koranic Ogam on a Colorado capstone. ESOP 11 (2), No.270: 211. Decipherment of the ancient writing from Etowah Mounds. ESOP 11 (2), No.273B: 233-234. A navigation grid or stick chart (Rebbelib) from the Marshall Islands, Micronesia. ESOP 11 (2), No.275: 237-240. (with Dexter, W.W.). Tifinag in Irish megalithic rock engravings. ESOP 11 (2), No.276: 241-244. (with Polansky, J.). A Polynesian artifact engraved with Libyan script. ESOP 11 (2), No.277: 245-250. Apparent Islamic influence at Runamo. ESOP 11(2), No.278: 251-255. (with Rudolph, J.H.). An Ogam inscription from Bainbridge Island, Washington. ESOP 11 (2), No.279: 256-257. 1984 The Galician Ogam consaine inscription at Prado da Rodela, northeast Portugal. ESOP 12 (1), No.280: 8-12. An ancient Arabic guide to Ogam on a sacred tablet from Zambia. ESOP 12 (1), No.284: 29-31. An Ogam consaine phallus from Britain. ESOP 12 (1), No.285: 32. The Bronze Age cult of Thunder Gods. ESOP 12 (1), No. 289: 65-70. Celtic augurs and Canada geese. ESOP 12 (1), No.296: 99-105 and foldout. New Mohamed petroglyph. ESOP 12 (2): 127. The Kinderhook Plates. ESOP 12 (2), No. 299: 132-141. Decipherment of the Lamboyeque [sic] Gold Plate. ESOP 12 (2), No.307: 206-207. 1985 Algonkian signatures on a treaty of A.D. 1681--Dr. Fell's report. ESOP 13, No.313: 22-26. An inscribed stone club in Syke Museum, Germany. ESOP 13: 26. ARMAVIRVMQVECANOTROIAEQVI PRIMVSARBORISITALIAMFATOPROFVGVS LAVINIAQVE. ESOP 13, No.315: 28-29. Ancient punctuation and the Los Lunas text. ESOP 13, No.317: 35-41. An inscribed brass casket of Dutch origin. ESOP 13: 51. Los Milagros-what are they? ESOP 13, No.320: 62. Decipherment of Flora Vista tablets. ESOP 14, No.337: 22-27. A new Bronze Age alphabet from Denmark. ESOP 14, No. 338: 28-30. Parietal [sic] inscriptions of the Anubis caves. ESOP 14, No.342: 45-60. Anubis-Lord of the Equinox, Keeper of the Balance. ESOP 14, No.349: 92-94. Norse Tifinag on an Iron Age bracteate. ESOP 14, No.350: 95. Ogam consaine coinage of the ancient Gauls. ESOP 14, No.351: 96-97. Inscribed bricks from Comalcalco, Mexico. ESOP 14, No.357: 118-125. Deciphering the Esmeralda Stone. ESOP 14, No.360: 129. The Atlatl Rock comet-a portent of death. ESOP 14, No.361: 130-131. Tifinag legends on Hiberno-Danish coins. ESOP 14, No.363: 134-135. Ogam consaine in western Scotland. ESOP 14, No.382: 135-138. Ogam-inscribed stone pendants from Nova Scotia. ESOP 14, No.384: 140-141. An Ogam Bricren inscription to the Horse Goddess. ESOP 14, No.385: 142-147. An Arabic Moslem text on an Anglo-Saxon coin. ESOP 14, No.388: 160-161. (with others). Red River Canyon, Kentucky. ESOP 14, No.387: 162-165. 1986 Runic inscription in Ludlow Cave South Dakota. ESOP 15: 20-21. Celtic or Keltic? ESOP 15: 24. Proto-Celtic at Lascaux. ESOP 15: 26. (with Meyer, H.C.). How old is the Cree syllabary? ESOP 15: 30. (with Bunce, W.H.). An Ogam-inscribed Atlatl-weight from Stillwater, New York. ESOP 15: 37-38. Review of: "Fantastic Archaeology: Alternate Views of the Past" by S. Williams. ESOP 15: 41. Pre-Columbian tobacco in India. ESOP 15: 46. Mediterranean mythology in traditional Pima chants. ESOP 15: 89-107. 1987 (with Atkinson, L.D.). An ancient star map in Jersey? ESOP 16: 17. An Ogam stone from Connecticut. ESOP 16: 18-19. Note on a Picasso coinage. ESOP 16: 23. Detecting fraudulent inscriptions. ESOP 16: 24. A Tifinag text at Tassili, Algeria. ESOP 16: 26-27. Ancient astrology of a cave in West Irian, New Guinea. ESOP 16: 84-90. Roman coin discoved in Ohio. ESOP 16: 90. (with Farley, G.). First American poem in Ogam script. ESOP 16: 96-97. Merry monks of Ireland. ESOP 16: 98-100. Dating the Basque inscriptions on rocks of the Susquehanna Valley. ESOP 16: 105-108. The Anglo-Saxon coinage in daily life. ESOP 16: 110-124. An Ogam consaine inscribed stone from Lewis Creek Mound, Virginia. ESOP 16: 127-129. Two Romano-British inscriptions. ESOP 16: 130-135. The Swastika in Celtic Britain and North America. ESOP 16: 136-141. (with Johanssen, C.L., Gonzales D., Ottonello, S., Powers, P., Parker, A., Ashraf, J.,& Loy, W.). The Tihosuco inscription retranslated as Spanish. ESOP 16: 142-145. Cabrilho's gravestone of 1543 recognised and deciphered. ESOP 16: 146-147. (with Payne, J.). Bar Creek No.2, Clay County, Kentucky 1987. ESOP 16: 150. (with Radloff, D.). Celtic rebus figures from the Upper Mississippi Valley. ESOP 16: 151-153. Ogam consaine in County Tyrone-Castlederg Cromlech revisited. ESOP 16: 301-303. An Aztec hieroglyphic paternoster. ESOP 16: 307-309. (with McCone A., Polansky, J. & Bloom, E.). The Lamina of Alcoy-background and current proposals. ESOP 16: 310-315. The Lamina of Alcoy-background and current proposals. Part 3--Spelling of place names. ESOP 16: 321. Inscribed stone artifacts from Guayanilla, Puerto Riceo. ESOP 16: 322-334. 1988 (with Dexter, W. & Farley, G.). Tanith with two scripts from South Africa. ESOP 17: 101-102. Susquehanna petroglyphs observed in 1820. Manuscript discovery in Delaware Museum. ESOP 17: 273. Bronze Age nordic traders in Canada. New light on Peterborough. ESOP 17: 274-275. A Christian North African inscription from Comalalco ESOP 17: 283-284. A Punic calendar from Comalalco. ESOP 17: 284-286. 1989 Caroline Islands script before the European contact. ESOP 18: 86-89. Deciphering the Easter Island tablets. Part 1. ESOP 18: 185-210. A Punic inscription on an Atlatl-weight from Georgia. ESOP 18: 321-325. Inscribed stone artifacts from Guayanilla, Pueto Rico. ESOP 18: 332-340. Shelta language on a pictish stele. ESOP 18: 342. Etymology of the Lower Mississippian languages-Part 1: Introduction. ESOP 19: 35-47. 1990 A revised date for the Pontotoc stele. ESOP 19: 60-62. Epigraphy of the Burrows Cave tablets. ESOP 19: 98-105. The origin of ESOP. ESOP 19: 147. Libyan alphabetic script on a Mexican cylinder seal. ESOP 19: 168. Four fraudulent Ogam inscriptions from Kentucky. ESOP 19: 213-216. Mediaeval elements in the Paris Basin petroglyphs. ESOP 19: 249. Deciphering the Easter Island tablets, Part 2. ESOP 19: 250-276. A Polynesian inscription from Tahiti. ESOP 19: 278-280. The Comalcalco bricks: Part 1, the Roman phase. ESOP 19: 299-336. 1991 Etymology of the Lower Mississippian languages-Part 2. ESOP 20: 43-90. Deciphering the Easter Island tablets, Part 3. ESOP 20: 122-145. Interpretation of the cast of a latex mold submitted by Gloria Farley. ESOP 20: 153. An Ogam solution to the agricultural grid symbol. ESOP 20: 154-155. Alphabetic Libyan mason's marks on Mochica adobe bricks. ESOP 20: 224-230. The Davenport stone. ESOP 20: 244. Origin of the Micronesian script. ESOP 20: 263-268. How to read an inscription upside-down. ESOP 20: 269. Deciphering the Easter Island tablets, Part 5; Maui and the Fire Goddess. ESOP 20: 31-40. Deciphering the Easter Island tablets, Part 6; powers of the tohunga. ESOP 20: 41-50. 1992 Takhelne, a Celtiberian language of North America. ESOP 21: 193-239. An ancient zodiac sign from Inyo, California. ESOP 21: 263-267. The Micmac manuscripts. ESOP 21: 295-320. 1993 Gauguin's crucifix, and its decipherment. ESOP 22: 34-38. The merchant fleet of ancient Iberia. ESOP 22: 45-46. A dialect of Minoan from Cyprus. ESOP 22: 67-70. The Ogam scales of the Book of Ballymote. ESOP 22: 87-132. Medical terminology of the Micmac and Abenaki languages. ESOP 22: 218-231. Ogam bricru in the Cimarron Valley. ESOP 22: 260 & 262. A Tifinag inscription in eastern Colorado. ESOP 22: 286. The Kinderhook Plates. ESOP 22: 319-326.

Click HERE to return to Equinox Project Web site.

© 2008The Equinox Project, All Rights Reserved. Compiled from the

contents of The Dawson Library

Created for and maintained by The Equinox Project Please email any comments, questions or suggestions to:

info4u@equinox-project.com

NOTE you must remove !!! from the suplied address before using.

Last Modified January 2010