Swansea, a multicultural petroglyph site in Inyo County, California

Roderick L. Schmidt

Lone Pine, California

The petroglyph site discussed in the following article is a mere ten miles from my home in Lone Pine. It has been my good fortune to spend much time there exploring and observing. It is subtle and complex, nearly every visit bringing something new to light. I owe much to the late Burrell Dawson and to his wife Margaret. We used to go there to witness the functioning of the vernal equinox marker so this paper is partly Burrell's doing, because of his careful critiques, suggestions and enthusiastic support.

The site was reported in Heizer and Baumhoff Prehistoric Rock Art of Nevada and Eastern California (1962). I never met Dr Robert Heizer. He had dedicated decades of his life to assembling sketches and photographs of petroglyphs and details of their locations. He believed that the American native peoples had evolved their cultures in isolation from the rest of the world, and therefore there were no outside influences from the Old World until after 1492.

In 1979 Dr Barry Fell reviewed Dr Heizer's published materials, and realized that some of the petroglyphs in California and Nevada showed clear evidence of Old World influence with particular reference to the Swansea area. Fell recognized that Heizer and Baumhoff had recorded an inscription in Kufic Arabic, together with a pictorial representation of the zodiac, though neither of the two authors had evidently recognized the true nature of their record. In search of fuller documentation Fell came to Berkeley from Harvard to consult with Heizer and to explain the decipherment of the Kufic. Heizer accepted Fell's explanation and it was then planned that a joint paper by Fell and Heizer would set out this change in interpretation of what had previously been supposed to be a purely local petroglyph devoid of astronomical or Arabic content. By misfortune, before publication was carried out, Heizer was overcome by fatal illness a month after Fell's visit to him. The resultant paper, in which Fell referred to Heizer's role, was published ESOP volume 8. An updated version of this paper is given in this volume (see preceding article). Though Burrell Dawson and Dr. Robert Heizer are no longer with us, this paper is dedicated to their memory.

The petroglyph site at Swansea discussed here is known by several names, Number 41, INY-272, and Swansea-Keeler group. It is important because it gives evidence of multiple cultural contacts and is a calendar regulation site. Since Barry Fell, epigrapher and President of the Epigraphic Society, deciphered over a dozen years ago, several inscriptions pecked into the dolomite marble much has been learned about the nature of the location. Yet, most of the site remains unexplained or misunderstood.

The markings at Swansea were created over a long period of time. Epigraphic evidence suggests a rough time frame of 3rd century B.C. to 1200 A.D. Dating accurately is extremely difficult. Several inscriptions have been maintained and repecked several times, the latest maintenance shows partial repatination. Many more have totally repatinated and are barely distinguishable.

In the course of its history scribes have used several methods to create the petroglyph designs. One technique was to abrade the surface patination to reveal the bright dolomite beneath. Another was to peck the rock to leave a groove and distinct edge to the work. Most of the work was done this way. One unusual design suggests that it was carved with a narrow blade to produce a fish. Whether any of the work was made with metal tools has not been scientifically established, nor has this question been raised by previous on-site explorers.

Who initiated the work is unknown. The natives with whom the first settlers came into contact were Shoshone-speaking Paiute people. Unfortunately their history and connection with Swansea was lost with the violent conflict over possession of the Owens Valley. The description of "hunter gatherer' was applied by anthropologists and ethnographers to these people' but in reality they were wildlife management and survival specialists.

The earliest post-Columbian explorers may have been Spanish or Mexican, but no surviving documentation backs this up. The first documented exploration was a detachment of the Fremont expedition which was conquering the new California Republic for annexation to the United States. The Walker Party traveled through and mapped the Owens Valley in 1845, followed shortly by miners, trappers and traders. For the next sixty years the valley was denuded of game and plundered for it's minerat riches.

In 1929 the ethnographer and anthropologist, Julian Steward, spent much time making a study of the natives and petroglyphs in the Owens Valley. He recorded the more obvious and clear inscriptions at Swansea and attempted to connect the site to a long abandoned native camp about a quarter mile to the south. Steward classified the site as belonging to the Great Basin style.

Two years later, Clifford Baldwin. accompanied by photographer, Carl Hegner, made another survey of Swansea. For what Baldwin recorded, epigraphers will be eternally grateful. He was a relatively unknown archaeologist hired by lnyo County to do a survey and his hand-prepared reports reside in the Eastern California Museum, Independence, California.

Jay C. von Werlhof surveyed the site in 1960. He suggested that the various petroglyph sites were somehow connected with migratory routes of game and went to great lengths to classify them as typical of the Great Basin in their style and elements.

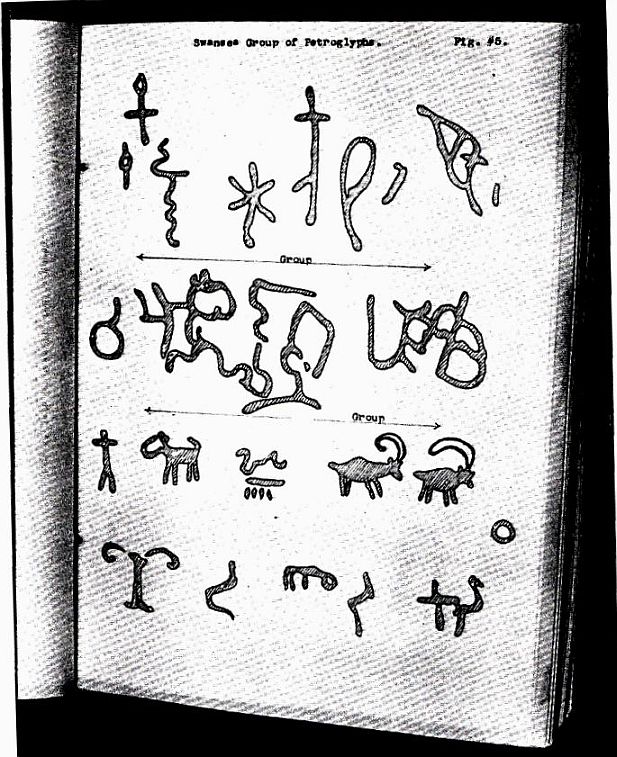

No one, Steward, Baldwin, or von Werlhof. made a survey that was even close to complete. The site is complex and each selected what he considered important. Baldwin regretted that he had so little time to spend there and he noted, "... these have some interesting designs, some of which were so faint they had to be traced painstakingly with the finger in order to reproduce them." (ref. figure 1)

The Inyo Zodiac

In 1962, The University of California Press published Prehistoric Rock Art of Nevada and Eastern California, a compilation of all available petroglyph data organized by Robert Heizer and Martin Baumhoff. Baldwin's sketches from Swansea were included and for the first time they were available to the general public, It. was in the "Prehistoric Rock Art" book that Dr. Fell recognized the lnyo zodiac and it's companion kufic inscription, it was probably an oversight, but Clifford Baldwin was not credited in the "Prehistoric Rock Art" publication.

The zodiac was accompanied by several lines' of poorly executed but recognizable Kufic script and the translation by Dr. Fell from Arabic proved to be significant. The message, "When the ram and the sun are in conjunction, then celebrate the festival of the new year," signifies the vernal equinox. Another inscription recorded by Baldwin less than ten meters away is a detail of the zodiac and Dr. Fell speculated that some unrecorded detail would indicate the beginning of the summer festival.

Later. Dr. Heizer and Dr. Fell made a sustained attempt to determine the source of the zodiac and the Kufic script in Dr. Heizer's book. but the painstaking search they made together through Dr. Heizer's files failed to do so. Recently it has emerged that Heizer's illustrations were certainly drawn from Baldwin's book.

It is worth noting that Dr. Heizer had, for many decades, disputed all diffusion theories. It was in connection with Dr. Fell's decipherment of the Inyo zodiac that Dr. Jon Polansky. who knew both of them, arranged for the two men to meet. After they met, Dr. Heizer recognized the authenticity of Dr. Fell's decipherment of the calendar aspects of the zodiac and the two men decided to publish a joint paper on the subject Heizer treating the zodiac and Fell dealing with the Kufic script. Tragically, Dr. Heizer died before this was accomplished. Later, Dr. Fell published his own monograph on the subject.

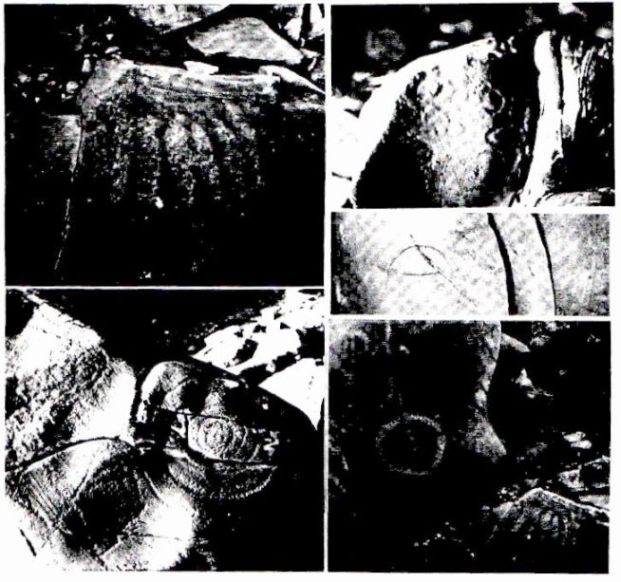

The Calendar Marks

Epigraphic researchers visited the site to find evidence to support Dr. Fell's decipherment The team of Dr. Jon Polansky, Alan Gillespie and others located the related marks that served the time keeping function. toward sunset on the equinox, a shadow creeps across a design of six roughly parallel lines and when the sun disappears below the skyline of the Sierra Nevada mountains it has exactly split the six lines. (ref. figure 2) Each tine unmistakably marked one day prior to or after the event. No one considered the possibility of Swansea being a calendar site before Dr. Fell. He made the predictions and they proved to be true.

The summer festival (summer solstice) indicator is different and even more spectacular. On the same freestanding boulder that the detail of the zodiac is pecked on, but on the obverse side is a series of concentric circles placed to take advantage of a natural window. Just prior to sundown. the face with the circles is in shadow except for a dagger of light which pierces the center of the circles (ref. figure 3). Because the dagger appears at sunset for several days, there may be yet another undiscovered detail that announced the exact day.

Another display of a sun dagger as a calendar regulator was created at Fajada Butte at the south entrance to Chaco Canyon, New Mexico and is attributed to the Anasazi, the mysterious pueblo builders. Although the culture has been the study of many archaeologists and ethnographers, it was an artist, Anna Sofaer, who is credited with the discovery of the calendar functions.

Burrell Dawson, Lone Pine resident and Fellow of the Epigraphic Society, located another calendar marker at Swansea, a circle that would be halved by the shadow of an overhanging rook at sunset on the equinox. The circle is very eroded indicating great age. Over time geologic movement and the elements have shifted the shadow making rock a little and it is no longer accurate.

Vincent Yoder, Lone Pine resident and companion of Burrell on many field trips, noted a sunrise marker that also indicated the equinox. In this case a pointer shadow marched across the center of a series of concentric circles. Observation on the day after the equinox proved the accuracy as the shadow misses the center by a small. but noticeable, margin. (To be the subject of a later paper.)

Earl Wilson, Lone Pine resident and geologist, noted that an alignment for visually sighting the summer solstice sunrise occurred on an adjacent boulder and we investigated his find. Sure enough, the sun rose nearly in line with what he predicted. This may be coincidence, but I think not. The observations and study are ongoing.

Alan Gillespie, geologist and researcher from the University of Washington, spent a lot of time recording and measuring with the hope of obtaining enough data to use archaeoastronomy to date the site. He discovered the sunset equinox marker and several cross quarter markers. These are three very similarly pecked and beautiful sun symbols, one has inscriptions in accompaniment. I observed one of these on the May cross quarter date. At sunrise, exactly one fourth of the design was lit by sunlight. The maker had observed the natural phenomena and placed his design in exactly the right spot for this to occur.

I visited the site early in November with the hope of seeing another of the cross quarter sun symbols react to the sunrise, but the one I had hoped would work did not. lt was entirely in shadow. What did work was that the rising sun lit a shallow series of lines on the north east corner of the summer festival boulder. These are so faint and repatinated that they had escaped earlier notice. The shadow of a large boulder to the east exactly split the lines.

There are at least a dozen other marks that may have time keeping functions. Most of these are very subtle and easily missed. Three are simply curved lines that match. a sunset or sunrise shadow of other nearby rocks. Another is a very pointed sunset shadow that centers on an asterisk shaped sun symbol accompanied by a carefully executed but undeciphered inscription.

Clifford Baldwin's original sketch

Upper left, equinox marker, compare text figure 2; lower left, summer festival marker, see text figure 3; upper right, kufic signature Zaiid Mohamed, see text figure 5; middle right, Christian ICHTHYS symbol, see text figure 6; lower right, inferred Christian Easter symbol, with equinox marker to lower right. (Photography by author).

The most often repeated motif on the site consists of several parallel lines, the most common number is six. Some may be native replications of the equinox marker while others may have calendar regulation functions. Earl Wilson noted an unusual series of connected circles and surmised that they may have midday functions, it will take much observation to sort all this out.

The Missing Zodiac

It took several visits to finally locate the important inscriptions related to the zodiac because they were so faint and repatinated. The team led by L. J. Dewald finally located them in 1984. The task would have been easier if the group had found Baldwin's book, because he describes the location well. What made the search for the zodiac itself futile was the fact that it was removed from the location some time after 1931. The conclusion reached by Dewald that it appears elsewhere on the site may be incorrect. The inscription noted in his ESOP report (Vol. 14 No. 377 pg. 202) as similar was probably a native reproduction of the original work. (The zodiac was sketched by Baldwin and appears in his book as Figure 5. The reproduction was photographed by Hegner and appears as plate 14.)

Celts, Moslems and Christians

Burrell Dawson before his death spent many hours researching the petroglyphs in the surrounding areas and made several discoveries suggesting that Celtic traders had traveled through the Owens Valley. At Swansea he located and translated a dedication to the Celtic god Lugh (ref. figure 4). Appropriately enough, Lugh was the Celtic god of light.

In late January, I was making a series of time lapse videos to record an obscure time keeping mark and while the camera was working noted a faint inscription that did not seem to have been previously recorded. lightly chalked the outline and photographed it for further study (ref. figure 5). The sketch made from the photograph was submitted to Dr. Fell for analysis and he reported back shortly that it appeared to be the graffiti signature of an Arab trader named Zaiid Mohammed. Mohammed is the most common name in the Arab world and Zaiid, variously spelled Zeid, Zayd or Zaid, occurs prominently throughout Arabic history.

The name Mohammed would certainly suggest an Islamic presence. The reference to the god Lugh would indicate a Druidic Celtic presence. still another presence is suggested by several distinctly Christian symbols that appear at Swansea; one of the symbols is still in modem use. Two arced lines intersecting in such a way as to generate the shape of a fish (ref. figure 6). This exists next to a well maintained, very deeply pecked circle, vertically intersected by a carefully depicted shepherds staff (ref. figure 7). According to Dr. Fell, the combination would suggest that the March equinox would signify the Easter Festival. This makes perfect sense because early Christian leaders utilized the timing of pagan festivals for the religious purposes of their own. The bisected circle would mean the balance of night and day (the equinox) and the shepherds staff is an ancient and well known symbol of Christianity.

Why Here?

The east side of the Owens Valley where Swansea is located did not seem as desolate to the ancient peoples as it does now, water was not scarce and game was. plentiful. What made the west side less preferable than the east was every canyon draining the Sierra Nevada Mountains was the source for deeply cutting creeks and streams making for many fords and dangerous crossings. The east side lacked these hazards.

A second possible reason is quite intriguing. In Saga America Dr. Fell reports on a petroglyph depicting what appears to be an ingot of silver complete with an assayers rectangle and the kufic Arabic marks for silver. The location of these inscriptions at Little Lake is a good day's walk to the south of the Swansea site. A similar version of the kufic silver marks and the stick figure of a man and a cross probably a representation of a pick or other tool was recorded at Swansea by Steward (ref. figure 8). Cerro Gordo, high up in the lnyo Mountains to the east of Swansea, was once Califomia's richest silver mine. The first known trail to Cerro Gordo came from Swansea.

Millions of dollars worth of ore was extracted from Cerro Gordo, milled, refined and shipped south to Los Angeles. It was incredibly rich but it's earliest days are undocumented and have a vague historic beginning. Legend has it that Pablo Flores began mining there sometime in early 1862. he and several unnamed companions were attacked by marauding Mojave natives and driven from the mountain. Of the two survivors, Flores made it to Independence and traded some of his silver for supplies. Victor Beaudry, owner of the store, visited the site afterward and seeing the great pits and trenches that covered the surface ore area, far too much work for the small number of miners that had worked for a single summer, suggested that Flores had been there before and mined some time earlier. The Mexican's used the same mining practices as the ancients, an open pit and vein-following technique locally called coyote mining.

At this point in time, the Owens lake was stable and full. The 1860 shoreline reaching the 3590 foot contour. It existed at this level until about the tum of the century when local farmers diverted much of the river flow for irrigation. The lake is now nearly dry. The full diversion of the river to the Los Angeles aqueduct was its final demise.

Recent discoveries on the lakebed show that ft had been quite dry and water level very low in prehistoric times. A culture that predated the Paiutes existed on the playa near fresh water springs and their camps were miles from the modem shoreline. Fairly near the 1860 shoreline one campsite is very notable.

Smelting Evidence

On a small spring mound surrounded by jasper, chert and basalt flakes (evidence of tool making) lies a surprising find. Slag, quite possibly from silver-lead ore, from a crude smelting operation and a small piece of an ancient fumace was found on the surface by the author in 1991. The quantity on the surface is small and the spread of slag is not very concentrated. It is possible that this is intrusive and belongs to the 1800's mining rush. but not likely. This area was under water during the mining of the late 1800's and was not exposed until well into the 1900's. Further study should reveal more clues.

This archaeological find is endangered by the Great Basin Unified Air Pollution Control District's plan to eliminate the hazardous dust that plagues the valley when the wind blows and creates a dust storm from the lakebed. The study they based their environmental protection effort on was created by a firm who never visited the site but read what archaeological data was available and incorrectly assumed that everything below the 3590 contour line was insignificant.

That this was a camp of ancient miners and traders is a distinct possibility. They would have employed native labor and this would account for the tool making evidence. The fact that no evidence of pottery was found is very curious and may be significant ft is important that a team of authorized archaeologists investigate this find and accurately date the materials recovered.

The Great Basin

Historical anthropologists and ethnographers imply by the category Great Basin that the petroglyphs were created by a single extensive culture. Evidence shows that this was not the case.

Swansea is not typical of Great Basin rock art. The multicultural contact is evident by the inscriptions left there. It is unfortunate that these were not recognized by the previous site recorders. Baldwin's quote. "...these have some very interesting designs.." show the most curiosity of any of the early investigators. His dedication to task left epigraphers a great clue as to how important Swansea is as a piece to the puzzle of diffusion and pre-Columbian transoceanic trade.

Sadly, there never has been a complete and careful record of the site. The "complete survey" as recorded in "Prehistoric Rock Art" is woefully incomplete. For example, ft shows 5 rayed sun symbols, in reality, no less than 9 appear on the site. The Zaiid Mohammed inscription was skipped as well as many others especially just outside the main concentration. Since the artwork and sketches varied so greatly between recording sources several designs are unintentionally duplicated. A new and more careful survey is necessary.

One of the most significant of the problems is the site destruction and lack of concen by the local Bureau of Land Management. Thieves have done significant damage, looting the zodiac from it's position next to the kufic inscription and damaging several of the sun symbols as well as the summer festival marker. However, the majority of the damage came sometime in the mid-1950's when a state contractor blew off the cliff face and crushed it for road fill. This is tragic as the petroglyphs in that section were never fully recorded. A ray of hope remains in the fact that Baldwin's photographer, Hegner, made a site record photograph of the cliff face and several prints are in existence. Perhaps a significant enlargement or computer enhanced analysis could add some of the lost data to the record. Clearly, the importance of Swansea cannot be underrated.

General References

Baldwin, Clifford Park (1931) Archaeological Exploration and Survey in Southern Inyo County, California Unpublished report.

Canby, Thomas Y.,(Nov. 1982) The Anasazi National Geographic Magazine

Dawson, Burrell C. (1986) The Swansea Ogam Unpublished Paper, The Dawson Collection.

Dawson Burrell C. and Yoder, Vincent (1985) The Horton Creek Site Volume 14, no. 381, pg. 209 Epigraphic Society Occasional Publications

Dewald, L.J. (1985) The Inyo, California Zodiac Volume 14, no 377, pg. 202 Epigraphic Society Occasional Publications

Fell, Barry (1989) America B.C. Pocket Books, New York. NY

Fell, Barry (1980) Saga America Times Books. New York. NY

Fell, Barry (1982) Bronze Age America Little, Brown and Company. Boston, Mass.

Fell, Barry (1980) An Ancient Zodiac From Inyo. California Volume 8. pan 1, no 179 pg. 9, Epigraphic Society Occasional Publications

Fell, Barry (1980) The Islamic Inscriptions of America Volume 8, Part 1, no 187, pg. 57. Epigraphic Society Occasional Publications

Heizer, Robert P. and Baumhoff, Martin A. (1962) Prehistoric Rock Art of Nevada and Eastern California University of California Press, Berkeley, California

Likes, R.C. (1975) From This Mountain Chalifant Press, Bishop. California

Steward, Julian (1929) University of California Publications in Archaeology and Ethnology Volume 24

Von Werlhof, Jay C. (1986) Rock Art of The Owens Valley. Reports of the University of Califomia Archaeological Survey, no 65

Yoder, Vincent (1985) Equinox Site at Swansea. Dawson Collection (Unpublished Paper).

RETURN TO EPIGRAPHY

© 2008The Equinox Project, All Rights Reserved. Compiled from the

contents of The Dawson Library

Created for and maintained by The Equinox Project Please email any comments, questions or suggestions to:

info4u@equinox-project.com

NOTE you must remove !!! from the suplied address before using.

Last Modified January 2010